| Henry's family details are available in my family files. |

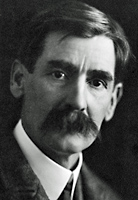

Henry Lawson (1867-1922), short story writer and balladist, was born on 17 June 1867 at Grenfell, New South Wales, eldest of four surviving children of Niels Hertzberg (Peter) Larsen, Norwegian-born miner, and his wife Louisa (nee Albury). Henry was given the Anglicised surname of Lawson in his birth registration. Peter was very unsettled, but took up a selection which Louisa managed; she also ran a post office in his name while he worked as a building contractor around Mudgee.

The young Lawson was often alone, often worried about the problems of the selection, and much disturbed by the apparent estrangement of his parents, a situation about which he was more knowledgeable than the younger children and which caused him keener suffering. Outside the family, he was one of those children who seem inevitably to become the butt for juvenile ridicule and cruelty. He had little opportunity for boyhood friendship and little talent for it when rare opportunities arose. He several times expressed to his father a reluctance to grow older even as worry, fears and oppression were denying him most of the joys of childhood.

Lawson was 8 before Louisa's vigorous agitation led to a school being established in the district, and he was 9 before he actually entered the slab-and-bark Eurunderee Public School as a pupil in the care of the new teacher John Tierney. In the same year, 1876, after a night of sickness and earache, he awoke one morning slightly deaf. For the next five years he suffered hearing deficiency. When he was 14 the condition deteriorated radically and he was left with a major and incurable hearing loss. For Lawson, already psychologically isolated, the deeper silence of partial deafness was a crushing blow.

When his much-interrupted schooling (three years all told) ended in 1880, Lawson worked with his father on local contract building jobs and then further afield in the Blue Mountains. In 1883, however, he joined his mother in Sydney at her request. Louisa had abandoned the selection and was living at Phillip Street with Henry's sister Gertrude and his brother Peter. He became apprenticed to Hudson Bros Ltd as a coachpainter and undertook night-class study towards matriculation. Yet, as the story ('Arvie Aspinall's Alarm Clock') which he based on that time of his life suggests, he was no happier in Sydney than he had been on the selection. His daily routine exhausted him, his workmates persecuted him and he failed the examinations. Over the next few years he tried or applied for various jobs with little success. Oppressed anew by his deafness, he went to Melbourne in 1887 in order to be treated at the Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital. The visit, happy in other ways, produced no cure for his affliction and thereafter Lawson seems to have resigned himself to living in the muffled and frustrating world of the deaf.

Meanwhile he had begun to write. Contact with his mother's radical friends imbued in him a fiery and ardent republicanism out of which grew his first published poem, 'A Song of the Republic' (Bulletin, 1 October 1887). He followed this with 'The Wreck of the Derry Castle' and 'Golden Gully', the latter growing partly out of memories of the diggings of his boyhood. By 1890 Lawson had achieved some reputation as a writer of verse, poems such as 'Faces in the Street', 'Andy's Gone With Cattle' and 'The Watch on the Kerb' being some of the more notable of that period.

Whether it was a matter of luck or temperament, Lawson seemed unable to attain equilibrium or direction in his writing or his lifestyle. His promising early poems had been followed by a rush of versifying on a wide range of topics, contemporary and reminiscent; and his first published story, 'His Father's Mate' (Bulletin, December 1888), though uneven and sentimental, had given glimpses of his extraordinary ability as a writer of short stories. By 1892 a number of sketches together with the magnificent 'The Drover's Wife' had fully borne out the initial promise. Yet Lawson seemed in a rut: failing to concentrate his energies and gifts much beyond what was required for subsistence, spending more and more time in favourite bars around Sydney. Recognising something of Lawson's inner faltering, J. F. Archibald suggested he take a trip inland at the Bulletin's expense. With five Pounds and a rail ticket to Bourke, he set out in September 1892 on what was to be one of the most important journeys of his life.

Much of what Lawson saw in the drought-blasted west of New South Wales during succeeding months appalled him. 'You can have no idea of the horrors of the country out here', he wrote to his aunt, 'men tramp and beg and live like dogs'. Nevertheless, the experience at Bourke itself and in surrounding districts through which he carried his swag absolutely overwhelmed him. By the time he returned to civilization, he was armed with memories and experiences —some of them comic but many shattering — that would furnish his writing for years. Short Stories in Prose and Verse, the selection of his work produced by Louisa on the Dawn press in 1894, brought together some of these stories albeit in unprepossessing form and flawed by misprints. But 'While the Billy Boils' (1896) was Lawson's first major short-story collection. It remains one of the great classics of Australian literature.

Within a year, however, Lawson seemed poised to achieve both the recognition and the stability he had been seeking. In 1895 he contracted to publish two books with Angus & Robertson; and he met Bertha Marie Louise Bredt (1876-1957), daughter of Bertha McNamara. After a brief and, on Lawson's part, characteristically intense and impulsive courtship, they were married on 15 April 1896. That year Angus and Robertson brought out the two books, In the Days when the World was Wide and other Verses and While the Billy Boils, as arranged; both were well received.

The Lawsons' move to Mangamaunu in the South Island of New Zealand was arranged by Bertha with the express intention of removing him from this kind of life. They left on 31 March 1897, but the venture was not a success, creatively or otherwise. Lawson's initial enthusiasm for the Maoris whom he taught at the lonely, primitive settlement soon waned. As well, there is evidence in some of his verse of that time ('Written Afterwards' and 'The Jolly Dead March') that he was realising, for perhaps the first time since their romantically rushed courtship and marriage and subsequent boisterous, crowded life in Western Australia and Sydney, both the responsibilities and the ties of his situation. Lawson's growing restiveness was deepened by promising letters from English publishers. Bertha's pregnancy strengthened his resolve and they left Mangamaunu in November 1897, returning to Sydney in March after Bertha's confinement.

Lawson went back to old friends and old ways in Sydney. He expressed a mounting sense of frustration and bitterness by drinking heavily — he entered a home for inebriates in November 1898 — and by writing a personal statement to the Bulletin. This appeared in the January 1899 issue under the title 'Pursuing Literature in Australia'. Abstemious and industrious throughout the ensuing year, Lawson worked on books contracted earlier with Angus & Robertson— On the Track and Over the Sliprails (stories) and Verses Popular and Humorous. But he would probably not have realised his goal of 'seeking London' had it not been for the generous help of David Scott Mitchell, the governor Earl Beauchamp and George Robertson. He set off on 20 April 1900 for England. With him went his wife, his son Joseph and his daughter of just over two months, Bertha.

Lawson himself in later years provided fuel for the idea that his English interlude, so eagerly anticipated, was in fact a catastrophe: 'Days in London like a nightmare'; 'That wild run to London/That wrecked and ruined me'. But he had some successes in London, the opportunity was certainly there for him to establish himself upon the literary scene and he may have been in some ways simply unlucky. But the strain of family life in unfamiliar surrounds and an unkind climate, his wife's serious illness (she spent three months from May 1901 in Bethlem Royal Hospital as a mental patient) and the consequent return to the soul-destroying task of writing under pressure to pay the bills, all sapped Lawson's early resilience and affected his health, the quality of his work and the nature of his literary aspirations and plans. By April 1902 he was arranging for Bertha to return home with the children. He followed soon after and they were all back in Sydney before the end of July.

From that time Lawson's personal and creative life entered upon a ghastly decline. A reconciliation with Bertha soon after their return was short lived. In December 1902 he attempted suicide. In April next year Bertha sought and obtained a decree for judicial separation. He wrote a great deal despite his often squalid circumstances but his work alternated between desperate revivals of old themes and inspirations and equally desperate and unsuccessful attempts to break new ground. Maudlin sentimentality and melodrama, often incipient even in some earlier work, invaded both his prose and poetry. Loyal friends arranged spells at Mallacoota, Victoria, (with Brady) in 1910 and at Leeton in 1916. But his state of mind, physical condition and alcoholism continued to worsen. The Commonwealth Literary Fund granted him one Pound a week pension from May 1920. He died of cerebral haemorrhage at Abbotsford on 2 September 1922.

Lawson was something of a legendary figure in his lifetime. Not surprisingly, as dignitaries and others gathered for his state funeral on 4 September, that legend was already beginning to flourish in various exotic ways. The result was that some of his achievements were inflated — he became known, for example, as a great poet — and others obscured. Lawson failed fully to assimilate one of the most vital inspirations of his writing life — his experience in the western outback. The decline of his creative ability, as it were before his very eyes, in the years from about 1902 onwards (though the malaise is traceable earlier than that in, for example, On the Track and Over the Sliprails, was one of the great tragedies of Lawson's troubled life.

His statue by George Lambert is in the Domain, Sydney; his portrait by Longstaff is in the Art Gallery of New South Wales and another by Norman Carter is at Parliament House, Canberra.