Why did these people decide in 1838 to leave the familiarity of their life in rural Sussex/Kent, where their family had lived for at least several generations, and emigrate with ten children halfway around the world to the primitive fledgling colony of New South Wales?

What did they experience during that voyage, and what was life like on their arrival in Sydney?

Despite the lack of family letters or other documents, we can attempt to answer some of these questions by looking at the history of those times.

In 1838, Victoria had been on the throne for only one year, and the Whig, Lord Melbourne, was Prime Minister. A country of fifteen and a half million people, England was economically and politically powerful, presiding as it was, over the Empire. The Industrial Revolution had commenced there in the previous century, prior to its spread to Europe and the United States, bringing with it significant affluence. Despite this, social conditions were terrible for the working person, and were publicised by writers such as Charles Dickens. His book `Oliver Twist', which graphically portrayed the poverty in the cities, was in fact published in 1838.

However, the Industrial Revolution had its greatest impact on rural society, which was breaking down as the cities grew. This had a severe effect upon traditional agricultural workers such as the Bowdens, Fairhalls and others. To worsen their plight, there were poor harvests nationwide in 1837, and the country experienced a sharp economic downturn in 1837 and 1838.

The life of the average English rural worker was extremely harsh, with little income, a poor quality of housing, no access to education, and no prospects of improvement for either himself or his children. For many, emigration to either Australia, North America or South Africa, was their only means of bettering their lot in life. Until the 1830's, however, emigration was actively discouraged by the government, as men were required for the American and European wars of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It was also considered that any loss of manpower would drastically weaken the English economy.

Several factors in the 1830's however, changed this negative attitude towards mass emigration. The population of England was growing so steadily that the eminent economist, Malthus, suggested that it would actually be in the interest of the country to encourage emigration. About the same time, Wakefield commenced a public movement to establish free, civilised colonies in Australia. This was associated with a growing public disquiet about the transportation of convicts, which was likened to the slave trade that had only been abolished in 1833. It was hoped that free emigration would end 'the leper-like ghastliness and deformity of convict society, and human barbarism of the Australian bush'. Additionally, many began to consider emigration to be a preferable alternative to the growing number of the poor being committed to the infamous `workhouses'.

These movements coincided with a drastic need in the colony of New South Wales for workers and, in particular, mechanics, craftsmen and agricultural labourers. The colony was developing rapidly, but progress had been slowed excessively by the shortage of such workers. Emigrants were required `to supply an abundance of cheap, honest and industrious labour'.

As a consequence, the first formal assisted emigration schemes to the colony were established in the mid-1830's. For a brief period, two emigration systems, the 'Government' and 'Bounty' Schemes, operated concurrently. The 'Government' Scheme, which ran from 1837 to 1840, under which the 'Maitland' was utilised, was the larger of the two, and was directed and financed by the British Government. The 'Bounty' Scheme (1835-1841) was organised by the colonial government of N.S.W. on behalf of the settlers who were dissatisfied with British government programmes. Prospective settlers were offered bounties as an incentive to emigrate. Both schemes, in fact, provided significant financial assistance to emigrate, as the cost of the passage was prohibitive for the majority of intending settlers. The assistance provided was similar under each scheme.

In 1838 the amount offered was:This meant that William and Anne Fairhall and their seven children, who came on the vessel 'Maitland', would have received 112 pounds to emigrate; a huge sum in those days when a rural worker might receive only 7s.6d. a week. The cost of these schemes was subsidised by the sale of land in New South Wales.

The Fairhalls aptly fitted the family grouping that was preferred for emigration. 'No families are better suited than those of which the parents, being 45 or even 50 years of age, have still power to work themselves, and at the same time can take out with them strong and healthy sons and daughters, of proper age to endure the mode of life at sea and to render themselves serviceable shortly after'. Emigrants of 'good moral character and industrious habits' were sought, and these had to present testimonials of their good character from a clergyman or other notable person from their region of origin.

The late 1830's was the first period of large-scale free emigration to New South Wales. In 1838, over 6,100 assisted emigrants made the journey. Despite the large scale of these schemes, they were smaller than the influxes of the 1850's Gold Rush era, when the population of the colonies increased dramatically.

|

Poor Law to Australia |

To Aust. & NZ |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Year |

Parishes |

Number |

Emigrants |

1837 |

15 |

341 |

5,054 |

1838 |

39 |

818 |

14,021 |

1839 |

38 |

558 |

15,786 |

1840 |

29 |

352 |

15,850 |

1841 |

32 |

353 |

32,625 |

1842 |

18 |

211 |

8,534 |

1843 |

16 |

200 |

3,478 |

1844 |

34 |

376 |

2,229 |

1845 |

11 |

149 |

830 |

1846 |

8 |

71 |

2,347 |

1847 |

14 |

117 |

4,949 |

TOTALS |

254 |

3,546 |

105,703 |

Years |

Parishes |

Totals |

|---|---|---|

1837/8 |

Bisley, Gloucestershire |

68 |

|

Rolvenden, Kent |

171 |

|

Sandhurst, Kent |

192 |

|

Beckley, Sussex |

68 |

|

Northiam, Sussex* |

117 |

1838/39 |

Benenden, Kent |

83 |

|

Beckley, Sussex |

57 |

|

Burwash, Sussex |

83 |

|

Framfield, Sussex |

80 |

1839/40 |

Saleshurst, Sussex * |

119 |

The major ports of embarkation to New South Wales were Birkenhead (near Liverpool), and Gravesend in Kent (near London), the place of departure for the 'Maitland's passengers. In the late 1830's, it was policy to have groups from the same region travel together in the ships. Many of those on the 'Maitland' in 1838 were from villages in Kent and East Sussex, as can be seen from the Passenger List of the 'Maitland'.

The journey was long and hazardous. During the emigrations of the nineteenth century, at least 26 ships were lost on the passage. In 1838, the route used to travel to New South Wales covered more than 13,000 nautical miles. The ships would stop at Capetown and perhaps Teneriffe (or the Cape Verde Islands) to replenish stocks of food and water. The 134 day journey of the 'Maitland' was faster than the usual five months of that era. The psychological and physical impact of such a long journey on the emigrants was considerable, particularly as many rural people, had barely ventured beyond their own rural district, let alone contemplated a lengthy sea passage.

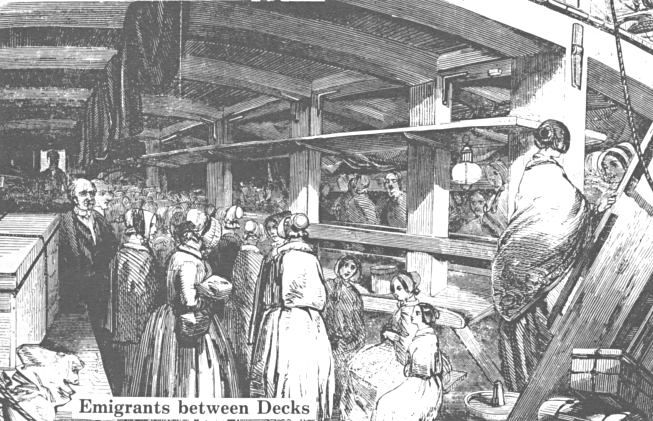

The arduous nature of the voyage was worsened by the poor standard of accommodation on the ships. Assisted emigrants, or 'steerage passengers', were housed in the lower decks, with only paying passengers living in the upper deck area. Married couples and children under 14 were in the centre of the lower decks, with the single women and girls in the 'after-berths', and the single males and boys in the 'fore part' of the ship. This would have meant that the three eldest Fairhall children were unlikely to have been with their parents during the journey, apart from seeing them on the upper deck during the day. The 'steerage quarters' were cramped, with only six feet and four inches (193 cm) of headroom. A meal table ran the length of the ship, with two levels of bunks on either side. These bunks were each three feet (91 cm) wide. Married couples would have an upper bunk, and up to four of the children the bunk below. The 18 inches (45 cm) width allowed for each person was identical to that which had been used in the convict transports.

Understandably there was limited privacy. Men were able to have saltwater showers on the upper deck, but many women did not bathe during the whole journey.

Those cramped unhygienic quarters encouraged the spread of infection. Some of the 'Government Scheme' ships, including the `Maitland', were notorious for the number of deaths due to infection. It was not until after the 1830's that strict regulations to ensure adequate hygiene were enforced to reduce death rates. Before that time, however, many passengers died from diseases such as scarlet fever, typhus and cholera. To avoid these tragedies, surgeons were appointed to each vessel to ensure adequate standards of hygiene and nutrition. Interestingly, they were also employed to select a suitable quality of migrant for the journey.

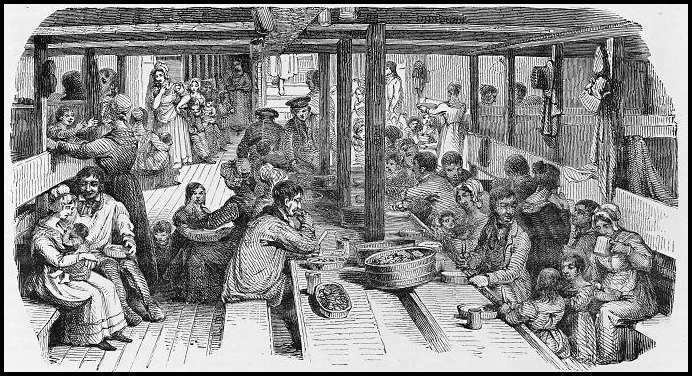

The above image is recorded as "Dinner on board the first emigrant ship for New Zealand [and] The Hutt river and bridge in 1855".

[Auckland, Star Lithographic Works, 1890], Reference Number A-109-054/055 from http://mp.natlib.govt.nz/detail/?id=9584.

However, in Charlwood, Don: The Long Farewell p110, it is recorded as being sourced

from the Illustrated London News, 10 May 1851, held by the National Library, Canberra

For meals, emigrants were grouped into a 'mess' of 6-12 people who were usually from the same neighbourhood, church or factory, and the print above shows families eating at a long table between their sleeping compartments. Friendships formed during these months, in such close quarters, were no doubt renewed later in New South Wales, and many of the 'Maitland' passengers, or their descendants, intermarried. A 'mess captain' would be selected to obtain the weekly rations and then take the food to the galley to be cooked. Meal rations varied from ship to ship, but were comprised of meat, bread, flour, suet, plums, rice, peas, coffee, tea, sugar, mustard and vinegar. Biscuits were also provided, but were often a source of complaint as they were frequently baked so hard they were impossible to eat. Prior to embarkation, emigrants were advised to bring jam and things to mix with the water when it gets stale!'.

The long journey was arduous and time hung heavily. When weather allowed, pastimes such as concerts and dances were arranged on deck, though strict supervision of the single males and females was always maintained! On Sundays, formal Church of England services were led on the upper deck, either by a clergyman or by the captain. Non-conformist or Catholic services were held below-decks. Many emigrants, such as the Fairhalls, could not write or could not read, or both, so teachers were often organised to take classes during the passage.

When the 'Maitland' arrived in Sydney on November 6th 1838, the colony of New South Wales was only 50 years old. Sir George Gipps was Governor of the colony, which at that time incorporated present-day Queensland and Victoria. New South Wales was still very much a convict settlement, with one of the largest military establishments in the British Empire. Convict transportation to the colony did not cease until January 1839, the month the Fairhalls were released from Quarantine.

The population of New South Wales was only about 80,000 and Sydney was just a small town of approximately 23,000 inhabitants. Half of the population were convicts or their descendants. The population was to double by 1841 due to the influx of free emigrants, by which time there would be four free persons for every bondsman. Brisbane (Moreton Bay) and Melbourne (Port Phillip) were only recently-established small settlements. Present-day N.S.W. and Victoria had been explored by Hume and Hovell, Sturt and Mitchell, but the explorations into Queensland, South Australia and Central Australia would not be undertaken until the 1840's.

Few buildings of the Sydney of 1838 remain standing in 1988. Amongst these are the Rum Hospital (present-day State Parliament House), the Mint, Convict Barracks, Government Stables (the modern 'Conservatorium of Music') and St. James Church in Macquarie Street.

In 1838, the colony had been in such severe drought that the Governor had proclaimed November 2nd (four days before the arrival of the 'Maitland') as a national day of 'fasting and humiliation'. It rained on November 4th, leading to an outbreak of influenza. These circumstances must have created an unpleasant welcome for the families from Kent and Sussex, who were having to contend with deaths of family members and a long period in quarantine. The drought conditions would have been a far cry from the lush green hop-growing regions of south-eastern England. Also at that time, there was major concern about frequent fights between the white settlers and the aboriginal population. Life in the bush was virtually lawless, and there were frequent reports of massacres by both whites and blacks.

The most difficult problem for all the new British settlers was, however, the sense of isolation due to the vast distance of the new colony from 'home'. Very few would ever be able to return, even if they had the means. Corresponding with relatives in Britain by mail took a minimum of 5 months one way, and about a year to receive a reply. Telegraphic communications did not connect Australia to the rest of the world until the 1870's.

Despite these difficulties, the new colony provided significant opportunities for men and women of enterprise, faith and industry. The rigid distinctions of the English class system had not been transferred to this new society. These factors allowed the families an opportunity to create lives that were more productive and fulfilling than would ever have been possible in their country of birth.